In Durban, South Africa’s third largest city, an amount of wastewater equivalent to 13 Olympic-sized swimming pools has been treated and reused for industrial use by a paper mill and a local refinery every day since 2001.

A public-private partnership (PPP) between the city and a private environmental services company made this achievement possible. And it is a good example of how wastewater reuse is helping some cities address critical water shortages.

Wastewater reuse — recycling and reusing water from our sewerage systems — may prompt what is quite simply known as the “yuck” factor. People are naturally squeamish about the idea of reusing water that comes from our toilets, even though it’s actually quite common. Wastewater reuse has been around for thousands of years.

This is also being done in Windhoek, Namibia, where a direct potable reuse scheme has been operating since 1965.

In other places, such as India, Singapore, Mexico and Spain, reused water can provide a valuable water source for key industries, reducing the demand on limited water resources. Power plants, refineries, mills, and factories, including, for instance, those in the auto industry, can use reused water.

The need is great. Not only do some 4.2 billion people around the world lack access to safely managed sanitation services, but 80 percent of global wastewater is not adequately treated. As much as 36 percent of the global population lives in water-scarce areas, and water demand is expected to rise to 55 percent by 2050 amid rapid urbanization.

At the same time, climate change is creating greater unpredictability and variability in the availability of fresh water. The United Nations estimates that 1.8 billion people will be living in countries or regions with absolute water scarcity by 2050, with Sub Saharan Africa counting the largest number of water-stressed countries of any region.

Countries affected by conflict and social fragility are especially vulnerable to water challenges and a deterioration of water services.

All of this matters because, as the World Bank says, gaps in access to water supply and sanitation are among the greatest risks to economic progress, poverty eradication and sustainable development.

Municipal waste and water is also an investment opportunity. An IFC analysis found that if cities in emerging markets focused on low-carbon water and waste as part of their post-COVID recovery, they would catalyze as much as $2 trillion in investments, and create over 23 million new jobs by 2030.

“An IFC analysis found that if cities in emerging markets focused on low-carbon water and waste as part of their post-COVID recovery, they would catalyze as much as $2 trillion in investments, and create over 23 million new jobs by 2030.”

It can provide a reliable water source for industrial, agricultural and — occasionally — potable uses, often at lower investment costs and with lower energy use than alternative sources, such as desalination or inter-basin water transfers.

Treatment of wastewater coupled with effluent reuse also has important direct climate benefits. In many cases, treating sewage water helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions, particularly methane. A well-designed wastewater project allows for better sludge management solutions, such as methane capture and energy generation, which help mitigate the greenhouse gas emissions coming from plants’ operations.

Moreover, water reuse can contribute to helping cities adapt to climate change by providing an additional and sustainable source of fresh water.

“Water reuse can contribute to helping cities adapt to climate change by providing an additional and sustainable source of fresh water.”

The majority of desalination projects globally are privately developed and financed. Yet, as national and local governments in emerging markets continue to face significant gaps in meeting water and sanitation needs and budgetary constraints, well-structured PPPs in wastewater treatment and reuse are increasingly seen as a viable option.

Water reuse projects do come with particular challenges. For one thing, water is a local matter and no one project is like another. Water is also typically managed at a decentralized level, where local utilities may lack resources and capacity, while perceptions of high risk and cost of capital can also raise concerns.

IFC sees an enormous opportunity to assist in this area. Through our new World Bank Group Scaling ReWater initiative,

Scaling ReWater is a toolkit offering transaction advice, competitive financing solutions, a more straightforward tendering process and a holistic approach designed to mobilize hybrid financing from public and private sources. Our overall objective is to leverage private capital to accelerate the construction of wastewater treatment plants in emerging markets. The World Bank Group welcomes the opportunity to work with our partners to achieve this.

Communities Turn to Reusing Wastewater

With the era of dam building coming to an end in much of the developed world, places such as California and Australia are turning to local and less expensive methods to deal with water scarcity, including recycling wastewater, capturing stormwater, and recharging aquifers.

Wastewater to Generate Electricity

Whether wastewater is full of “waste” is a matter of perspective. “Why is it waste?” asked Zhen He, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis. “It’s organic materials,” he said, and those can provide energy in a number of ways. Then there’s the other valuable resource in wastewater. Water.

Want a more sustainable world? Let women lead the way

Women are increasingly driving the global economy. According to a 2009 Harvard Business Review article, women controlled $20 trillion in consumer spending each year. Morgan Stanley reports that women control $11.2 trillion of the United States’ investable assets, too — assets held in one’s bank account, stocks, bonds and certificates of deposit.

Off-Grid Living Systems

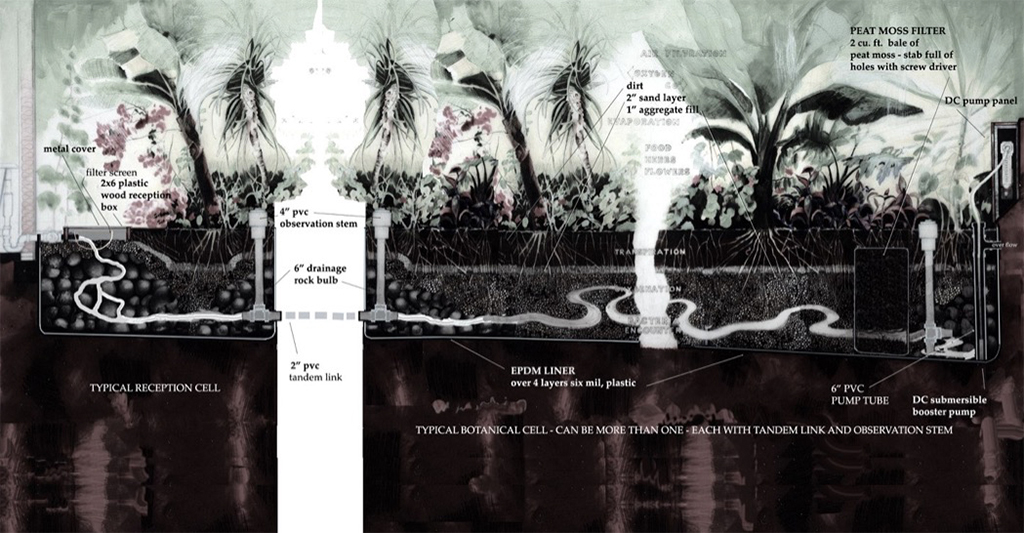

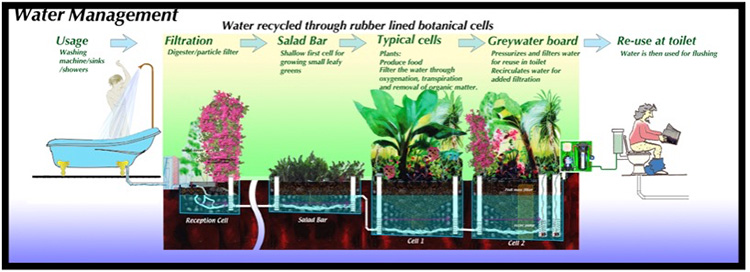

Water | Power | Waste Water Treatment | Heating/Cooling

The systems of a building. These are the systems that go into the structural shell of the building for occupancy. Some or all of these systems can be used instead of the conventional methods to provide utilities to buildings. This can make the build more sustainable, secure and healthy than only using conventional utilities.

All systems can have automated conventional backups. All systems can be added to existing conventional buildings as a renovation project.

Living with sustainable off-grid systems enhances our lives, secures our lives and is a better investment than conventional buildings.

This increases both psychological and physiological comfort.

Leave A Comment